Chinese perceptions of the border crisis, jostling in the Indian Ocean, and a Cantonese Hindi romance

Welcome to today’s The India China Newsletter.

In this issue, I’ll be looking at:

- Chinese perceptions of the border crisis and the current state of relations with India

- India and China jostling in the Indian Ocean, and Pakistan’s chief of naval staff speaks to the Global Times

- China's financial sector reforms: a view from India

- Why Chinese 'liberals' love Trump

- The first bilingual Cantonese-Hindi film

Mathieu Duchatel has an excellent piece giving a great overview of how different leading Chinese strategic experts have looked at last year’s border crisis with India, what led to the crisis, and the current state of relations (thanks to Taylor Fravel for bringing this to my attention on Twitter).

It’s worth reading in full. Here are a few points that caught my attention and some observations:

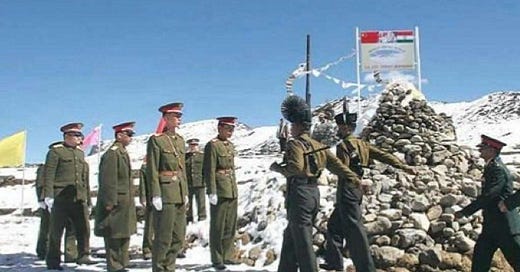

Not surprisingly, the main narrative in China regarding the origins of the clashes is to put the blame on India. The red thread running through Chinese analyses is to argue that Indian behavior has forced China to abandon its longstanding practice of self-restraint in managing the disputed border.

No article presents a detailed factual chronology of events to back their claims, and the words “People’s Liberation Army (PLA)” are almost never mentioned - their aim is clearly not to offer insights into the operations of the PLA. There are however two specific accusations directed at Indian troops. First, Hu Shisheng argues that the recklessness of the Indian border troops commander was the immediate sparkle that started the fire in the Galwan Valley last June. This echoes the view often made by the Chinese side in track 2 discussions.

Second, the August counteroffensive in the Pangong Tso lake area led the Indian military to seize control over some heights surrounding the lake. Lin Minwang argues that the operation was aiming at gaining leverage in the ongoing talks with China. It was conducted despite five rounds of meetings at the level of military-commanders that were succeeding in cooling down the border tensions after mid-June 2020 and had led to disengagement in some places.

The India-U.S. angle has been quite prominent in most of the analysis, as this newsletter noted on January 29. Duchatel writes:

Indeed, all Chinese analyses converge on the key importance of US-India relations in explaining tensions. What is going away, according to Su Jingxiang, is India’s tradition of neutrality and non-alignment. India is becoming – of its own free will – a “frontline country” (前线国家) in the emerging “anti-China alliance” (反华联盟) built by the United States.

The mirror-imaging in arguments on both sides is really striking. The first is with regard to who violated the border agreements that have helped keep the peace for the past 28 years:

Su Jingxiang from CICIR interprets this decision as the latest outcome of a longstanding and systematic policy of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in power, that aims at the destruction of the foundations of India-China border management. Prior to the 2020 clashes, two agreements constrained the military forces of the two sides: the 1993 Agreement on the Mainte- nance of Peace and Tranquility along the Line of Actual Control in the India- China Border Areas 29, and the 1996 Agreement between India and China on Confidence-Building Measures in the Military Field along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas. 30 The second text obliged the two signatories to refrain from using firearms within two kilometers of the LAC.

The second is with regard to both accusing the other of trying to redraw the LAC:

Yang Siling argues that the Indian military considers the Galwan Valley a gateway to Aksai Chin. Liu Zongyi is less categoric – he sees India taking advantage of strategic cooperation with the United States and aiming to revise the existing Line of Actual Control , but India’s specific operational goals are left to speculate. Hu Shisheng is the only expert to provide a military balance tactical explanation to back his argument that the Indian side started the clashes. He argues that India has perceived the Chinese “border defense infrastructure activities” (边防基建活动) in the Galwan Valley area as a threat to the newly built 55-kilometers road between Darbuk, Shyok and Daulat Beg Oldie, the only land access for Indian forces to reach the Siachen glacier.

And the important conclusion:

The collection of Chinese views analyzed for this piece suggests that Chinese actions are determined by a macro view of relations with India, and ultimately aim at affecting great power competition with the United States.

Elizabeth Roche reports in Mint:

India on Thursday expressed its readiness to share military hardware, including missiles and electronic warfare systems, with countries in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) where China has been increasingly raising its profile in recent years.

Speaking at the opening session of the day-long IOR Defence Ministers' Conclave in Bengaluru, on the sidelines of the Aero India show, Singh said India’s aim of holding the meet was to "synergise the resources and efforts in the Indian Ocean, including, defence Industry industrial cooperation amongst participating countries."

Former Foreign Secretary Vijay Gokhale writes on how India looks at China’s ambitions in the region:

The balance of power in the Indian Ocean is undergoing a significant change as countries from outside the region begin to establish a permanent presence there.

In the past 10 years, the biggest change has been the sharp escalation in China’s naval activities in the northern Indian Ocean, including through its hydrographic surveys in the exclusive economic zones of littoral states, growing deployment of submarines and unmanned underwater drones, and establishment of its first overseas military facility in Djibouti.

If this is the beginning of a larger Chinese naval presence throughout the Indian Ocean, a close examination of China’s intentions and behaviour is warranted.

China claims that its naval activities are normal and reasonable and assures the rest of the world that it will never seek hegemony.

When the Chinese say that they will not exercise hegemony, they presumably mean not the American kind. They are not seeking to assume the role of a paramount state that uses its power and influence to impose rules and order on an otherwise anarchic world. Pax Britannica is not for them either. They have shown no appetite to directly control large tracts outside the homeland or to carry the flag, as David Livingstone did, for ‘Christianity, commerce and civilization’.

Exercising the sort of hegemony that the Soviet Union did is entirely ruled out. The lessons of Soviet failure due to overreach in the export of communism globally are compulsory reading for all members of the Chinese Communist Party.

What China seeks is the pursuit of national self-interest through persistent and consistent actions to become the dominant state in the Indo-Pacific. The shape of possible Chinese hegemony may be uniquely Chinese in character—a kind of Chinese hegemony with socialist characteristics.

Pakistan's chief of naval staff has given an interview to Global Times welcoming the PLA Navy’s presence in the region to ‘maintain the regional balance of power’ (ie, balance India):

Pakistan's maritime security is intertwined with the maritime environment in the Indian Ocean region which is rapidly transforming. In our immediate neighborhood, long drawn instability in Afghanistan simmers and continues to impinge upon regional security. On our eastern side, India, with an expansionist mindset, is destabilizing the region by actions that could imperil regional security.

On our Western flank, the US-Iran standoff has vacillated, posing risks to ships plying along the international Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs). The ongoing conflicts in Yemen and Syria are also impacting regional maritime security. The warring groups' access to shore-based missiles and remotely operated vehicles is a serious threat to SLOCs transiting the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden…

The PN and PLA Navy with their longstanding and expanding cooperation can play an important role in maintaining good order at sea. The PLA Navy's presence in the Indian Ocean region is thus an important element in maintaining the regional balance of power and promoting maritime security.

On whether China is building a naval base in Gwadar, he says:

Gwadar is a commercial port that will serve as the lynchpin of the CPEC project. As the port gets fully operational, like any other commercial port, it may also receive port calls by ships of different navies. Karachi Port, for example, receives ships of different navies quite often. Visit of a commercial port by naval ships does not alter the commercial nature of the project. Moreover, the PN is taking all possible measures to ensure protection of Gwadar Port and its seaward approaches through sustained presence in and around the adjoining waters off Gwadar.

Former Foreign Secretary Shyam Saran on the significance of China’s recent financial sector reforms offering greater participation to foreign entities into China’s large and expanding banking, insurance and financial services industry:

These opportunities are well-timed as China offers returns that are unavailable in the rest of the world, particularly in the post-pandemic economic environment. Among large economies, only China will register a positive growth in gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020 of about 2-3 per cent.

We are witnessing a wave of integration of China’s financial market with the West-dominated global financial system. There is swift coupling rather than decoupling here; we may be at the cusp of a massive reordering of the system with major impacts on the global economy and geopolitics.

Chinese financial reforms have the obvious economic purpose of attracting large financial flows into its expanding economy but also to make its financial markets aligned with global norms and management practices. China also recognises the huge attraction that its financial markets have become for western financial firms, including US banking and securities companies. The bigger the stake they come to acquire in China, the greater the leverage China will have in the unfolding geopolitical game. Here is an emerging interdependence that could be “weaponised” in future, just as we have seen in the goods trade.

An interesting conversation between Ling Li and Teng Biao exploring the love that Chinese “liberals” have for Trump:

Because the point of reference in China is the communist system, any policies resembling those in the capitalist system will be considered ‘right’ and any policies that advance communist agendas will be ‘left’. Even though party ideology has changed significantly during the past four decades—in particular, shifting from demonising capitalism to embracing it—the labels remain the same. If you are supporting the Party, you are on the left and if you are against the Party, you are identified as being on the right. Clidas take great pride in being identified as on the ‘right’ simply because of their anti-party stance. They further apply their understanding of the left in the Chinese context to the left-wing politics of the West, which, in their minds, is not much different from advocacy of communism, including absolute distributive equality, mass movements, governmental intervention, class struggle, etc.

The conversation also refers to the emergence of the curious “baizuo” or “white left” term and links to this fascinating piece by Chenchen Zhang on how this became a Chinese Internet result — the Chinese version, if you will, of this lovely term I’ve been called more than once on Twitter — ‘libtard’.

And finally…

The South China Morning Post reports on what’s possibly the first Cantonese-Hindi bilingual film that’s been shot entirely in Hong Kong. It apparently features a Bollywood-style number shot in the middle of Central, which is for me a good enough reason to find a way to see it:

My Indian Boyfriend, a cross-cultural love story about a young Indian man and a Hong Kong Chinese woman, was filmed entirely in Hong Kong during the pandemic. Slated for release in India and Hong Kong in March/April, the film – the first bilingual movie to be made in Cantonese and Hindi – is a romantic drama replete with song-and-dance sequences in true Bollywood style.

The film follows the story of Krishna, the son of Indian immigrants in Hong Kong, played by debutant Karan Cholia, and a young Hong Kong Chinese woman, Jasmine, played by well-known local actress Shirley Chan Yan-yin. The pair live in the same neighbourhood and fall in love. However, drama begins when their families learn of their dalliance. All hell breaks loose and the couple encounter many obstacles along the way.

Thank you for reading! Have a great weekend, and the newsletter will be back on Monday.